The theory of the formation of the solar system presented in p. 8.2 above was developed before the discovery of exoplanets. One of the tests of the correctness of a theory is how well the theory agrees with later discoveries in the field. We can therefore ask whether the properties of the discovered exoplanets are consistent with the presented theory of the formation of the solar system. To do this, we must first look at what these discovered exoplanets are.

Eksoplaneedid paistavad meile äärmiselt nõrkadena ning nende niigi nõrk heledus on tugevalt varjutatud nende tähe heledusega. NASA kodulehe (https://exoplanets.nasa.gov) järgi on 2024 aasta augusti seisuga teada umbes 5600 eksoplaneeti, millele lisandub üle 9000 eksoplaneedi kandidaadi. Üks teine andmebaas (http://exoplanet.eu) annab pisut erinevad arvu, umbes teadaolevat 7300 eksoplaneeti. Igal juhul on see arv üsna suur.

Esimesed kaks eksoplaneeti avastati 1992. aastal ühe pulsari ümber. Esimene eksoplaneet Päikese-sarnase peajada tähe (51 Pegasus) ümber avastati 1995. aastal Šveitsi astronoomide Michel Mayori ja Didier Quelozi poolt, kes said avastuse eest 2019. aastal Nobeli füüsikapreemia. Planeedi tähis on 51 Peg b ja tema nimeks on pandud Dimidium. Planeedi mass on 0,5 Jupiteri massi ja ta asub tähest 0,05 aü kaugusel, st väga lähedal.

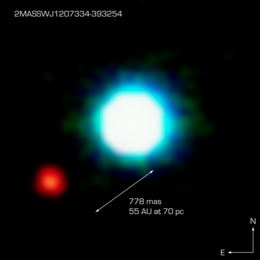

Joonisel 199 on üks esimesi otsese pildistamisega avastatud eksoplaneet. Planeet on veidi massiivsem Jupiterist ja tiirleb üsna väikese heledusega pruuni kääbuse ümber. Pruuni kääbuse nõrk heledus tegigi võimalikuks seda planeeti otse näha.

Eksoplaneetide avastamiseks kasutatakse põhiliselt kahte meetodit: radiaalkiiruse meetodil (sh 51 Peg b) ja näiva heleduse muutumise meetodil. Esimesel meetodil on leitud umbes 900 planeeti, teisel meetodil umbes 3800 planeeti. Lisaks on 50−60 planeeti ka otse avastatud. See viimane annab muidugi kõige enam infot. Tugeva panuse on juba andnud James Webbi kosmoseteleskoop ja loota võib, et väga olulise lisa annavad ka tulevase Euroopa Lõunaobservatooriumi ELT teleskoobi vaatlused. Loodetakse ka, et gravitatsioonilise mikroläätse efekti abil hakatakse eksoplaneete leidma mitmetes teistes galaktikates. Erinevatest meetodidest saab ülevaate NASA interneti lehelt https://exoplanets.nasa.gov/alien-worlds/ways-to-find-a-planet/?intent=021# .

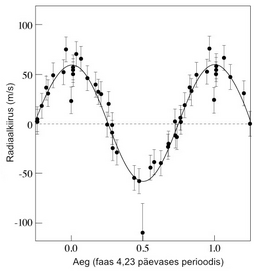

Radiaalkiiruste meetod on oma olemuselt sama, mis kaksiktähtede puhul spektroskoopiliste kaksiktähtede avastamise meetod (vt p. 5.1.5). Lihtsalt kaksiku teine komponent on nüüd väga nõrk ja väikese massiga. Tähe spektrist mõõdetud vaatleja suunaliste kiiruse võbelemised on seetõttu samuti väga väikesed. Mida massiivsem on planeet ja mida lähemal ta tähele tiirleb, seda kergemini on kiiruste võbelemised avastatavad. Näiteks 51 Peg puhul olid kiiruste muutused vaid 50 m/s perioodiga 4,2 päeva (joonis 200). Lihtsalt võrdluseks: Jupiter tingib Päikese kiiruse võbelemise 12 m/s. Kuid nii nagu kaksiktähtede puhul, nii tuleb ka siin arvestada, et registreeritav vaatesuunaline kiirus ei ole sama, mis tegelik ruumkiirus. Ehk siis saadav planeedi mass võib tegelikult olla suurem, kui tuleb sellest meetodist. Mitmiksüsteemide puhul võib radiaalkiiruste andmete tõlgendamine olla üsna keeruline.

Näiva heleduse muutumise (või varjutuse) meetod on samuti oma olemuselt sama, mis kaksiktähtede varjutusmuutlike kaksiktähtede avastamise meetod. Ent taas, planeetide väikeste mõõtmete tõttu on tähtede heleduste muutused väga väikesed, parimal juhul 0,1 tähesuurust, tavaliselt pigem 0,01 tähesuurust ja vähemgi. Kui samaaegselt õnnestub mõõta tähe radiaalkiiruste muutuseid ja heleduse muutuseid, on vaatejoon planeedi orbiidi tasandis ning hinnangud planeedi massile täpsemad.

Meetod eeldab väga täpseid mõõtmisi ning parem on neid sooritada kosmosest. Märkimist väärivad kolm satelliiti. Euroopa satelliit CoRoT (Convection, Rotation and planetary Transit, http://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Space_Science/COROT_overview ) töötas aastatel 2007-2012 aastal ja jälgis enam kui 120 tuhande tähe heleduse fluktuatsioone. Satelliidi abil leiti hulgaliselt kaksiktähti, aga ka 34 kindlat eksoplaneeti. NASA kosmoseteleskoop Kepler (https://science.nasa.gov/mission/kepler) töötas 2009−2013 ja jälgis samuti umbes tähte. Kuna Kepleri teleskoop oli suurem ja orbiit sobivam, siis leidis umbes 2600 planeeti. Praeguseni käib Kepleri andmete järeltöötlus. NASA satelliit TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, https://exoplanets.nasa.gov/tess/) startis 2018. aastal ja töötab praeguseni. TESSi andmete uurimine alles käib, kuid hulgaliselt planeete on juba ka leitud.

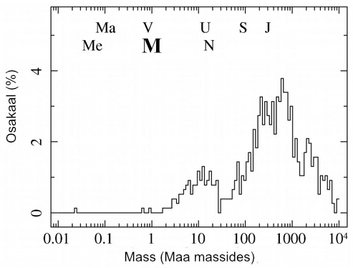

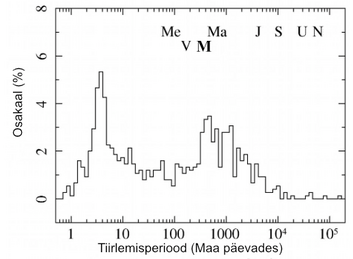

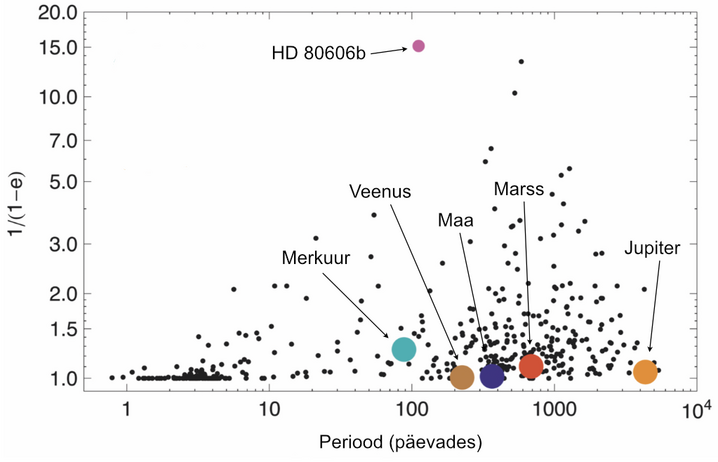

Joonistel 201 ja 202 on teadaolevate eksoplaneetide masside ja (elliptiliste) orbiitide perioodide jaotus. Masside jaotuse joonisel on ülaosas ka meie planeetide masside asukohad tähistatud planeetide nimetähtedega.

| Joonis 201. Eksoplaneetide masside jaotus Maa massi ühikutes. Joonise ülaosas on võrdlusena toodud ka päikesesüsteemi planeetide masside asukohad (Maa on pisut paksema tähisega). Allikas: http://exoplanets.co/exoplanet-correlations/exoplanets-mass-distribution.html | Joonis 202. Eksoplaneetide tiirlemisperioodide jaotus Maa päevades. Joonise ülaosas on võrdlusena toodud ka päikesesüsteemi planeetide perioodide asukohad (Maa tähis on pisut paksema tähisega). Allikas: http://exoplanets.co/exoplanet-correlations/exoplanets-period-distribution.html |

Masside jaotusel on huvitav piir Maa massi. Teoreetilistest arvutustest tuleneb, et umbes selline mass on vajalik, et planeet suudaks hakata koguma enda ümber gaasi ja moodustada gaasilise hiidplaneedi. Sellest väiksemate masside puhul on tegemist arvatavasti kivimilise planeediga. Teiseks tinglikuks piiriks loetakse Maa massi, sest sellest piirist väiksemaid objekte samastatakse Maa-sarnaste planeetidega.

Tiirlemisperioodid on vastavalt Kepleri seadusele seotud planeedi kaugusega tähest. Planeete, mis asuvad tähest kuni kaugusel, nimetatakse kuumadeks ning kaugemaid planeete külmadeks. Eraldusjoon on muidugi tinglik, kuna planeedi temperatuur sõltub väga oluliselt tema tähe omadustest.

Enamik eksoplaneete langeb nn "külmade Jupiteride" või "külmade Neptuunide" kategooriasse, ehkki nad paiknevad oma tähele lähemal kui päikesesüsteemi Jupiter ja Neptuun. Küllalt oluline kogus planeete on aga "kuumad". Arvestades nende tähtede omadusi võib hinnata nende pinnatemperatuurideks

Paarkümmend planeeti on Maa-sarnased. Mitmed neist on aga tähele lähedal ehk "kuumadel" orbiitidel, st me ei tahaks seal elada. Iga tähe puhul on võimalik arvutada välja ligikaudne asustatuse piirkond, mille olulisim omadus on vedela vee võimalikkus. Hetkel ei saa kindlalt öelda, et sarnaseid eksoplaneete on avastatud, ehkki umbes kümme kandidaati on olemas. Nende massid on küll korda suuremad Maa massist.

To date, about 10% of the stars studied have planets, with about 20% having more than one planet. The most numerous system so far is a system of seven planets. Considering how difficult it is to discover exoplanets, we can say that the discovery confirms that the formation of stars and planets around them is the same process. The existence of planetary systems around stars is a common phenomenon.

In order to start comparing the statistical properties of discovered exoplanets with the properties of the solar system, we should first accept that the statistics of exoplanets are sufficiently representative to be free of significant bias. Unfortunately, we must immediately state here that this requirement is far from being satisfied. On the contrary, the sample of exoplanets we know is strongly biased. The detection methods used preferentially allow the detection of massive planets that are located quite close to the star. Let us recall the radial velocity diagram of 51 Peg b. The measurement errors of the speeds there were about 10 m/s. Currently, the accuracy of the measurements has been obtained to be 1−2 m/s. We noted that Jupiter causes a disturbance in the speed of the Sun of 12 m/s, but Neptune only 0.5 m/s and Earth 0.1 m/s. In other words, we would only be able to detect the presence of Jupiter around a nearby star, but Earth would certainly remain undiscovered. We would not be able to notice Earth even through eclipses.

There is still a long way to go to gather data to get reliable and slightly less biased statistics. However, the study of exoplanets is currently very relevant, and several future space missions are dedicated to it.

But what about the elongated orbits of exoplanets (Fig. 203). Here we cannot say that our methods primarily allow us to detect such orbits, although there is a certain bias. Although the planets of the solar system have fairly circular orbits, the theory of their formation also allows for non-circular orbits. There are several ways in which massive planets acquire elongated orbits in the processes of the formation of the solar system. Quite the opposite, in calculations of the formation of the solar system, it has been a problem how Jupiter's orbit has remained so stable in a circular shape. During their formation, planets have repeatedly passed close to other (proto)planets and moved to various elongated orbits. It is likely that some planets have been thrown out of the solar system altogether.

So, for the theory, eccentric orbits are not a problem. However, this fact must be taken into account if we want to search for stable Earth-like planets. If in such a planetary system there is a planet with the mass of Jupiter in a rather eccentric orbit, then this will certainly affect the stability of the other orbits. In the solar system, however, Jupiter's circular orbit is, on the contrary, of a stabilizing nature.

The existence of "hot Jupiters" is also consistent with the existing theory. When a massive planet forms in a gas disk (as has happened in the Solar System), such a planet loses its orbital energy as a result of dynamic friction and gradually migrates inward. Such migration has probably also occurred in the Solar System, although not to such a large extent. Sufficiently fast migration works as long as the stellar wind does not blow away the gas disk. This is probably the main difference between systems with "hot Jupiters" and the Solar System - the intensity of the initial stellar wind and the time of its occurrence. Since both of these can vary, it can be expected that the speed of migration can also vary. In many cases, the existence of "hot Jupiters" is therefore also possible. In fact, similar migration was theoretically predicted even before the first "hot Jupiters" were discovered. However, the cause of migration can also be the gravitational interaction of a massive planet with another massive planet. We must always keep in mind that exoplanet detection methods primarily detect planets that are large and close to the star. Therefore, the number of "hot Jupiters" found is strongly biased towards finding them.

Exoplanets

Many planets have been found near other stars. Multi-planet systems have also been found.

Searching for exoplanets

To search for planets, one tries to find small periodic changes in the brightness of the star being studied (eclipses) or periodic changes in the wavelengths of spectral lines (Doppler shifts of orbital motions). Some exoplanets have also been found by direct observations.

What exoplanets have been found

The masses of the exoplanets found so far are mostly 10 to a few thousand Earth masses. Their orbital periods mostly correspond to distances from the central star of 0.1−5 AU. About twenty planets are roughly Earth-like. Planets with possible liquid water have not yet been definitively discovered.