Learning focus: | Forces arise when two objects interact; the force on one object is always equal in size, and opposite in direction to the force on the other object; force arrows indicate the size, direction and location of each force. |

Observable learning outcome: | Label force arrows to describe the action of the force: ‘force exerted on [object A] by [object B]’. |

Question type: | Simple multiple-choice |

Key words: | Force |

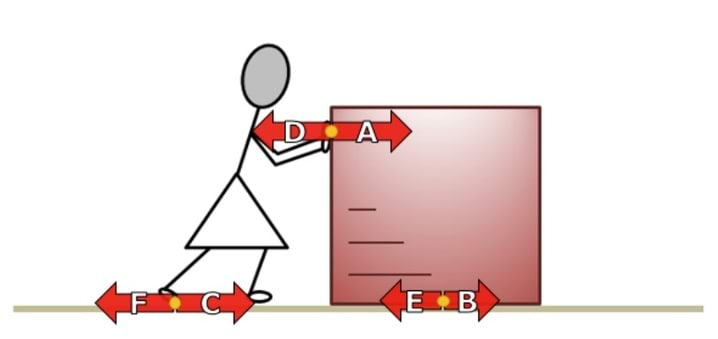

Interpreting force diagrams, to find out what happens to an object, requires students to identify which of the forces are acting on that object. Naming the forces, for example ‘electrostatic’ or ‘push’, does not help.

Through their research, Erickson and Hobbs (1978) found that using activities in which students are asked to describe forces in terms of the force of object A pushing on object B can improve the recognition and understanding of which forces act on a particular object.

The diagram used in this diagnostic question shows three ‘paired forces’. Driver et al (1994) found evidence that students don’t generally recognise the ‘reaction’ force in a situation. Force arrows and descriptors of the reaction forces have been included in this question to help make them more familiar to students.

Students should complete the question individually. This could be a pencil and paper exercise, or you could use an electronic ‘voting system’ or mini white boards and the PowerPoint presentation.

The worksheet works best if both pages are copied onto one side of A4 paper.

The answers to the question will show you whether students understood the concept sufficiently well to apply it correctly.

If there is a range of answers, you may choose to respond through structured class discussion. Ask one student to explain why they gave the answer they did; ask another student to explain why they agree with them; ask another to explain why they disagree, and so on. This sort of discussion gives students the opportunity to explore their thinking and for you to really understand their learning needs.

Differentiation

You may choose to read the questions to the class, so that everyone can focus on the science. In some situations it may be more appropriate for a teaching assistant to read for one or two students.

Question 1: descriptions A and B are both correct, but incomplete descriptions and of other forces could be described in exactly the same way. Description C can only be the force indicated. Description D is the reaction force to Molly pushing on the box.

Question 2 has the same responses as question 1. A and B are incomplete and D describes the reaction force. To imagine this force, ask students to picture Molly standing on a loose rug. As she pushes with her foot, the rug will be pushed backwards.

Question 3: forces described in A and B are pushing in the wrong direction. Students giving answer C may be attributing forces to ‘active’ objects that can make themselves move. In this case: Molly pushes on the box and makes it move, the box then pushes on the floor. A loose rug on the floor would be pushed forwards.

If students have difficulty in describing forces, it would be helpful to give them further examples of forces to label. This response often works best in pairs or small groups, as discussion encourages social construction of new ideas through dialogue.

The following BEST ‘response activities’ could also be used in follow-up to this diagnostic question:

- Response activity: Adding weight Response activity: Holding a weight

Driver, R., Squires, A., Rushworth, P. and Wood-Robinson, V. (1994) Making sense of secondary science, research into children’s ideas, Routledge, London, England.

Erickson, G. and Hobbs, E. (1978) ‘The developmental study of student beliefs about force concepts’, Paper presented to the 1978 Annual Convention of the Canadian Society for the Study of Education. 2 June, London, Ontario, Canada.